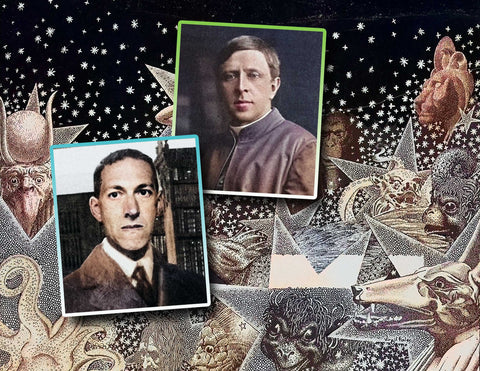

Black Seas of Infinity: Cosmic Horror According to H. P. Lovecraft and R. H. Benson

For the title page of his ghost story collection, A Mirror of Shalott, Monsignor Robert Hugh Benson chose the Latin phrase — “Primus est deorum cultus deos credere.” This is drawn from Seneca. It states:

“The first way to give cultus to the gods is to believe in the gods.”

Why would Monsignor Benson apply this dictum to ghost stories?

One possibility is that supernatural tales produce in the reader — even in the reader not given to religious orthodoxy — a state of mind capable of belief in the supernatural. We offer to the weird tale what Coleridge termed a “willing suspension of disbelief.” In other words, one must become like a little child in order to enjoy a good ghost story. If the author, then, is adept at atmosphere, character, and plot, we find ourselves involved, believing — and so we fulfill, if only for a few minutes, the first way to give cultus to the gods.

Reading a ghost story, we also experience wonder, awe, and terror — the interior effects, if you will, of belief or of a bonafide supernatural encounter.

It so happens that one particular author of the weird tale, Howard Phillips Lovecraft, wanted nothing to do with belief. Yet, at the same time, he deeply loved the interior effects of fictional supernatural encounters. It was Lovecraft’s special genius to contrive a way to have his cake and eat it, too — that is, to describe encounters that are not supernatural, yet that produce wonder, awe, and terror.

We call the resulting sub-genre “cosmic horror.”

Beyond Freedom and Dignity

Lovecraft was an atheist. More specifically, he espoused philosophical materialism. The logic of this worldview goes like this:

-

Reality consists solely of matter and energy.

-

Matter and energy are subject to the physical laws of the universe.

-

Human beings, too, consist solely of matter and energy.

-

Human beings, therefore, are subject entirely to the physical laws of the universe.

The result is that our so-called “actions” are as determined as the tides.

You can add complexity to the situation all you like. From the lowliest amoeba to the grasshopper, from Schlitzie the Pinhead to Robin Williams, utter determinism remains the end result. Our sense of free action, in this view, is entirely illusory. You do what you do not because a mixture of instincts and influences leads to a razor’s edge moment of actual choice, but because — at the end of a series of completely accidental actions and reactions — something simply “clicks.”

By accident is meant: no God, no design, no meaning.

Imagine, for a moment, what falls into place if human freedom does not exist. There was never a primordial choice that separated man from God. There is no basis for saying a man who steals deserves punishment; no basis for saying a man who lays down his life for another deserves praise. There is no possibility of moving toward the sacred – not merely because the sacred does not exist, but because an existing, self-aware you capable of choosing the sacred does not exist.

Imagine, too, how such a philosophical commitment affects the individual devoted to ghost stories.

On the one hand, he is convinced that science has supplanted religion and that science supports an entirely deterministic worldview. On the other hand, he is drawn to the numinous, to mystery – which he imbibes through stories that insist we do not merely shut off like a lightbulb when we die, from tales that describe a supernatural landscape of ghosts, demons, and who knows what else. The whole point of the thing is that something impinges upon what we do understand with an agency and intention that we (decidedly) do not understand.

How, then, could Lovecraft retain awe and mystery while jettisoning supernatural belief?

From Ghosts to “Entities”

In his essay, “Supernatural Horror in Literature,” Lovecraft distinguishes between “the literature of mere physical fear and the mundanely gruesome” and the “true weird tale [that] has something more than secret murder, bloody bones, or a sheeted form clanking chains...”

In the true weird tale, “a certain atmosphere of breathless and unexplainable dread of outer, unknown forces must be present; and there must be a hint, expressed with a seriousness and portentousness becoming its subject, of that most terrible conception of the human brain — a malign and particular suspension or defeat of those fixed laws of Nature which are our only safeguard against the assaults of chaos and the daemons of unplumbed space.”

From the first paragraph of his essay, it is plain that fear pertaining to the “fixed laws of Nature” is what Lovecraft savors. It isn’t fear of physical harm or even death. It isn’t fear of a pagan or EC comics sort — in which the dead sit in judgment and can upend our lives if they become vengeful and angry. It is, instead, a fear peculiar to the scientific age: what if the theories scientific method uncovers, the physical laws that drive the cogs and wheels of the technology-driven “grid,” the givens that form our very way of thinking are not as hardwired into reality as we think?

In the supernatural tales of the past, the living comprised a “closed system.” The arrival of the ghost opened up vistas of unending mystery. In Lovecraft’s world, circumscribed by science, nature is a closed system; nothing beyond nature exists. However, there remain the “the daemons of unplumbed space.” Who could say whether, light-years distant, there are not “hidden and fathomless worlds of strange life which may pulsate in the gulfs beyond the stars,” aspects of reality so utterly alien that they might “press hideously upon our own globe in unholy dimensions which only the dead and the moonstruck can glimpse”?

In other words, what if utterly alien and contrary physical laws came into contact with our own? While a deterministic worldview might prompt a person to look out at the world as if everything is predictable, everything is “known,” the intrusion of some utterly alien aspect of that same closed system might dwarf such pretensions, might destroy such complacency. In its extreme Otherness, such an intrusion might appear to act as in pre-scientific times a hurricane once seemed to act. Modern man, though immersed in philosophical materialism, might experience something akin to what pre-modern man felt — when the wind seemed to move of its own inscrutable accord.

Lovecraft experimented with such notions in tales like “The Colour Out of Space” and assigned names to such forces in stories like “The Call of Cthulhu.” The human protagonists in a Lovecraft tale — mired, as Lovecraft would say of his Catholic acquaintance, August Derleth, in the old, meaningful, religious view of things — might apply a lens of Good and Evil to events. In fact, pop culture has turned “dread Cthulhu” into a Scooby Doo villain – an acting, choosing “person” who merely schemes and manipulates on a more extraterrestrial scale. This all reflects, in Lovecraft’s view, the mistaken tendency “to attribute intent and personality to the formless, infinite, unchanging and unchangeable void.”

For Lovecraft, nature remains a closed system; horror has been exported to the outer realms of that same system. When we touch that outer realm, the comfort of the world we know disappears. Cthulhu, Yog Sothoth, Shub-Niggurath — these represent the cognitive intrusion William Shatner experienced when he went into space. According to the account published October 22, 2022 on variety.com, this is what “Captain Kirk” saw when he stared out the port window of Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin space shuttle:

“I…turned my head to face the other direction [from Earth], to stare into space. I love the mystery of the universe. I love all the questions that have come to us over thousands of years of exploration and hypotheses. Stars exploding years ago, their light traveling to us years later; black holes absorbing energy; satellites showing us entire galaxies in areas thought to be devoid of matter entirely… all of that has thrilled me for years… but when I looked in the opposite direction [from Earth], into space, there was no mystery, no majestic awe to behold . . . all I saw was death.

“I saw a cold, dark, black emptiness. It was unlike any blackness you can see or feel on Earth. It was deep, enveloping, all-encompassing. I turned back toward the light of home. I could see the curvature of Earth, the beige of the desert, the white of the clouds and the blue of the sky. It was life. Nurturing, sustaining, life. Mother Earth. Gaia. And I was leaving her.

“Everything I had thought was wrong. Everything I had expected to see was wrong.”

Shatner returned from his trip into space intent upon action — to nurture life on Earth and encourage understanding between its disparate peoples. Lovecraft, wholly committed to determinism, could not emphasize social action. Instead, his eyes remained fixed on the black gulf of space: “The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.”

A Return to Ghosts

Of course, Robert Hugh Benson, a Catholic convert and prominent apologist as well as ghost story writer, had something else in mind.

His characters, often Catholic priests, deal in human freedom — actions for which we are truly responsible, choices that ally the human soul either to the sacred or to the diabolical.

Such priests are armed with reason, the virtues, the Sacraments — and with the Deposit of Faith, which functions as a map. A Lovecraft-like tension arrives, however, when the map, it turns out, does not describe ALL of reality. Neither the duck-billed platypus nor the ghost receives official treatment. Benson’s stories involve the latter because encounters with duck-billed platypuses do not imply what encounters with ghosts imply: our radical smallness, the alien immensity of the fallen angels, the possibility of losing the path delineated on the map, what might happen to us if we encounter what the map does not bother to describe.

This introduces something like Lovecraft’s “black seas of infinity,” something like what Shatner experienced when he stared out into Deep Space. M. R. James once observed about ghosts — “Some of these things are so, but we do not know the rules!” In a similar vein, one of Benson’s priests, Monsignor Maxwell, declares, “Here is this exceedingly small earth, certainly with a very fair number of people living on it—but absolutely a mere fraction of the number of intelligences that are in existence. And all about us—since we must use that phrase—is a spiritual world, compared with which the present generation is as a family of ants in the middle of London. Things happen—this spiritual world is crammed full of energy and movement and affairs… We know practically nothing of it at all, except those few main principles which are called the Catholic Faith—nothing else.”

Monsignor Maxwell is speaking of the supernatural. A priest who has had a paranormal encounter insists the encounter must make sense, must have been intended in some manner that fits what he understands — otherwise, why did Providence allow it?

Monsignor Maxwell replies, “What conceivable right have we to demand that the little glimpses that we seem to get sometimes of the spiritual world are given us for our benefit? …My religion teaches me that there is a spiritual world of indefinite size, and that things not only may, but must, go on there which have nothing in particular to do with me. Every now and then I get a glimpse of some of these things—an orange pip, at the very least. But I don’t immediately demand an explanation. It probably isn’t deliberately meant for me at all. It has something to do with affairs of which I know nothing, and which manage to get on quite well without me.”

And finally, “My dear Father, no one in this world has a greater respect for, or confidence in, dogmatic theology than myself; in fact, I may say that it is the only thing which I do have confidence in. But I respect the limits which it itself has laid down.”

In this, Benson evokes something of what Lovecraft was looking for — “There [should] be excited in the reader a profound sense of dread, and of contact with unknown spheres and powers; a subtle attitude of awed listening, as if for the beating of black wings or the scratching of outside shapes and entities on the known universe’s utmost rim.” Benson’s characters do encounter the Unknown with a capital “U.” The difference is that in Robert Hugh Benson’s view the very principle of reason itself, the Divine Logos that created both the shores of Earth and the black expanse of space, is a Person. And that Person cares for us.

The gulf between the finite and the infinite — deeply disturbing to Lovecraft (and Shatner) since it appears to relegate humanity to absolute futility — this gulf has been bridged by the Incarnation. The cosmic principle of reason decided not only to approach mankind but to come to us as a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes and cradled in a feeding trough — a gesture of such outrageous humility that it turns smallness and futility on its head. And the gulf between the sinner and the holy — an expanse that prompted Isaiah to cry, “Woe is me, for I am undone! Because I am a man of unclean lips, and I dwell in the midst of a people of unclean lips; for my eyes have seen the King, The LORD of hosts” — this was bridged when the same incarnate Logos willingly died on the cross “to give His life as a ransom for many.”

Although M. R. James found his friend, Robert Hugh Benson’s, tales “too clerical” for his taste, Dewi Evens, a lecturer in Victorian literature at Brunel University, disagrees: “R.H. Benson’s supernatural fiction has been accused of being nothing more than thinly-veiled Catholic propaganda. This is only half true. For while his ghost stories present and promote an ontology that is rigidly Catholic, it would be churlish to dismiss them as nothing more than mere dogma. In his second collection of uncanny tales, the stories succeed through a carefully heightened sense of unease and mounting horror. Despite the underlying religious certainty, several of the tales also skillfully evoke the ‘cosmic’ horror of the weird fiction tradition, revealing an unseen world in which uncontrollable forces, immeasurably more powerful and more ancient than humanity, are locked in a constant struggle.”

Which brings us back to traditional ghosts.

It’s too bad Lovecraft never applied logic to the strongly apparent existence of freedom in man. He might have run across the following possible conclusions regarding ghosts:

-

If matter and energy are subject entirely to the physical laws of the universe, and if man (nevertheless) clearly demonstrates free action, it must be the case that some aspect of man is not subject to these physical laws. We might term this aspect of man “beyond-the-natural” or “super-natural.”

-

It follows that the “beyond-the-natural” is also not subject to entropy — that is, to death and decay. What becomes of this aspect of man after the body, subject to entropy, has given up? It would persist.

-

It appears this element of freedom pertains only to persons. That is, we do not associate freedom of action with trees or grasshoppers. It is persons, then, that persist after the body gives up. These are traditionally termed “eternal spirits.”

-

There are no apparent means for the “over-the-natural” to proceed from the natural; it makes more sense to posit that the “over-the-natural” proceeds from an original source that is itself “over-the-natural.” This would be personal as well. All in all, this personal source of the “over-the-natural” corresponds to the traditional idea of “God, the father of spirits.”

-

Given our experience of persons, it would seem appropriate for this “God, the father of spirits” to extend some effort toward communication. He might even “come down to our level” in some manner.

Perhaps the seas of infinity are not so “black” after all.